Gebruiker:Notum-sit/Germaanse religie

De Germaanse religie was de religie van de Germaanse volkeren, voordat zij in de middeleeuwen (gedwongen danwel vrijwillig) overgingen tot het christendom. De Germaanse religie was een polytheïstische religie.

Van de Germaanse religie is de noordelijke variant uit Scandinavië het best bekend dankzij de laat-middeleeuwse geschriften waarin de Noordse mythologie werd opgeschreven. Ook over de religie van de Angelsaksen, en het Europese vasteland, gewoonlijk aangeduid met Continentaal-Germaanse religie, zijn echter in beperkte mate schriftelijke bronnen bekend. De oudste schriftelijke informatie stamt van de Romeinse schrijvers rond het begin van de jaartelling. Volgens Tacitus hadden de Germanen toen zelf nog géén schriftelijke cultuur voor hun overlevering.

De schriftelijke vermeldingen worden gecomplementeerd door archeologische vondsten en het voortleven van elementen in de folklore.

Algemeen karakter[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Het geloof van de Germaanse stammen had een polytheïstisch karakter. Oorspronkelijk werden de goden vereerd in bossen, bij bronnen en ..... In Tacitus' tijd vonden de Germanen het nog niet gepast tempels voor hun goden te bouwen. In latere eeuwen bouwde men wel tempels, de bekendste daarvan is die van Uppsala. Men vereerde de goden met offers. Dit gebeurde zowel door het offeren van dieren als mensen. De hoofdgod was Wodan (of Odin zoals hij in de Noordse mythologie heet). Sommige onderzoekers menen op grond van vergelijkingen met andere Indo-Europese culturen dat oorspronkelijk de god *Tiwaz (de Noordse god Týr) de hoofdgod moet zijn geweest

Oudheid[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

De kennis van de religie ten tijde van rond de jaartelling is vooral te danken aan twee schrijvers: Julius Caesar en Tacitus. Over de periode daarvoor kan alleen gespeculeerd worden aan de hand van archeologische vondsten en vergelijking met andere religies.

Caesar[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

De oudste schriftelijke meldingen over de religie van de Germanen zijn te vinden in de De bello Gallico van Julius Caesar. Hij stelt de "primitieve" religieuze Germaanse gewoonten tegenover die van de Galliërs: "De Germanen verschillen veel van deze gewoonte. Want ze hebben noch druiden die de heilige zaken leiden, noch geven ze veel aandacht aan offers. Onder het getal van hun goden noemen zij alleen hen die ze kunnen waarnemen en door wier hulp ze klaarblijkelijk worden bijgestaan, Zon en Vuur en Maan, de overigen kennen ze zelfs niet van horen zeggen."[1]

Dit zou betekenen dat de Germanen rond 50 v.Chr. een natuurreligie hadden. Wetenschappers hechten tegenwoordig weinig waarde aan deze observatie. Een eeuw later beschrijft Tacitus in elk geval een heel andere religieuze cultuur.

Tacitus[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Veel uitvoeriger beschrijft Publius Cornelius Tacitus de Germaanse gewoonten in zijn Germania, informatie die hij overigens niet uit eerste hand had. De Germania stamt uit de eerste eeuw n.Chr.

Tacitus stelt de hoofdgod der Germanen gelijk aan Mercurius, aan wie ook mensen worden geofferd. Dieren worden geofferd aan goden die Tacitus gelijkstelt aan Hercules en Mars. De Sueven offerden ook aan een godin waarin Tacitus overeenkomsten met Isis zag door een van haar attributen, een Liburnisch schip.

Verder geloofden de Germanen dat hun goden hen bijstonden in de oorlog. Daarom namen ze afbeeldingen en voorwerpen mee uit hun heilige wouden. Het waren dan ook de priesters die de strijders mochten terechtstellen, gevangen laten zetten of doen geselen.

Another goddess, Nerthus, is revered as the Earth Mother by Reudignians, Aviones, Angles, Varinians, Eudoses, Suardones and Nuithones. Nerthus is believed to directly interpose in human affairs. Her sanctuary is on an island, specifically in a wood called Castum. A chariot covered with a curtain is dedicated to the goddess, and only the high priest may touch it. The priest is capable of seeing the goddess enter the chariot. Drawn by cows, the chariot travels around the countryside and wherever the goddess visits, a great feast is held. During the travel of the goddess, these tribes do not go to war and touch no arms. When the priest declares that the goddess is tired of conversation with mortals, the chariot returns and is washed, together with the curtains, in a secret lake. The goddess is also washed. The slaves who administer this purification are afterwards thrown into the lake.[5]

According to Tacitus, the Germanic tribes think of temples as being unsuitable habitations for gods, and they do not represent them as idols in human shape. Instead of temples, they consecrate woods or groves to individual gods.

Divination and augury was very popular:

To the use of lots and auguries, they are addicted beyond all other nations. Their method of divining by lots is exceedingly simple. From a tree which bears fruit they cut a twig, and divide it into two small pieces. These they distinguish by so many several marks, and throw them at random and without order upon a white garment. Then the Priest of the community, if for the public the lots are consulted, or the father of a family about a private concern, after he has solemnly invoked the Gods, with eyes lifted up to heaven, takes up every piece thrice, and having done thus forms a judgment according to the marks before made. If the chances have proved forbidding, they are no more consulted upon the same affair during the same day: even when they are inviting, yet, for confirmation, the faith of auguries too is tried. Yea, here also is the known practice of divining events from the voices and flight of birds. But to this nation it is peculiar, to learn presages and admonitions divine from horses also. These are nourished by the State in the same sacred woods and groves, all milk-white and employed in no earthly labour. These yoked in the holy chariot, are accompanied by the Priest and the King, or the Chief of the Community, who both carefully observed his actions and neighing. Nor in any sort of augury is more faith and assurance reposed, not by the populace only, but even by the nobles, even by the Priests. These account themselves the ministers of the Gods, and the horses privy to his will. They have likewise another method of divination, whence to learn the issue of great and mighty wars. From the nation with whom they are at war they contrive, it avails not how, to gain a captive: him they engage in combat with one selected from amongst themselves, each armed after the manner of his country, and according as the victory falls to this or to the other, gather a presage of the whole.

The reputation of Tacitus' Germania is somewhat marred as a historical source by the writer's rhetorical tendencies. The main purpose of his writing seems to be to hold up examples of virtue and vice for his fellow Romans rather than give a truthful ethnographic or historical account, although modern day scholars are reverting this point of view as unholdable.[6] But while Tacitus' interpretations are sometimes dubious, the names and basic facts he reports are credible; Tacitus touches on several elements of Germanic culture known from later sources. Human and animal sacrifice is attested by archaeological evidence and medieval sources. Rituals tied to natural features are found both in medieval sources and in Nordic folklore. A ritual chariot or wagon as described by Tacitus was excavated in the Oseberg find. Sources from medieval times until the 19th century point to divination by making predictions or finding the will of the gods from randomized phenomena as an obsession of Germanic cultures. Or as Tacitus puts it "To the use of lots and auguries, they are addicted beyond all other nations."

While there is rich archaeological and linguistic evidence of earlier Germanic religious ideas, these sources are all mute, and cannot be interpreted with much confidence. Seen in light of what we know about the medieval survival of the Germanic religions as practiced by the Nordic nations, some educated guesses may be made. However, the presence of marked regional differences make generalization of any such reconstructed belief or practice a risky venture.

- Divinatie

- Offers

- priesters

- vereringsplaatsen

- Goden

- archeologie

- parallellen met Romeinse goden

Oost-Germaanse volken[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Langobarden[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

In de Origo gentis Langobardorum uit de 7e eeuw wordt de herkomst van de naam van de Oost-Germaanse stam der Langobarden verklaard door een mythe. Toen de Langobarden met hun buren de Vandalen vochten hielp de godin Frea hen tegen de Vandalen die Frea's echtgenoot Godan aan hun zijde hadden.[2]

Gothen[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Het weinige wat over de religie van de Gothen bekend is, voor zij zich tot het arianisme zouden bekeren, is overgeleverd in de Getica van Jordanes (ovl. na 552), een 6e-eeuwse Gotische geschiedschrijver. Hij schrijft dat de priesters, net als de koningen, uit de adel afkomstig waren. De Gothen vereerden de oorlogsgod Mars aan wie ze krijgsgevangenen offerden. Ook offerden ze hem het beste van de buit en hingen ze te zijner eer de wapens van de vijand op aan bomen.[3] Jordanes vermengde echter de geschiedenissen van de Geten (verwant aan de Thraciërs) en de Gothen, zodat niet duidelijk is op welk van beide volken dit slaat.[bron?]

Europees continent[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

http://www.northvegr.org/lore/grimmst/b001.php

Superst. B

SUPERSTITIONS - B

B. Indiculus superstitionum et paganiarum (at the end of the Capitulare Karlomanni of 743 apud Liptinas. (1) Pertz 3, 20).

- I. de sacrilegio ad sepulchra mortuorum.

- II. de sacrilegio super defunctos, id est dadsisas.

- III. de spurcalibus in Februario.

- IV. de casulis, id est fanis.

- V. de sacrilegiis per ecclesias.

- VI. de sacris silvarum quas nimidas vocant.

- VII. de his quae faciunt super petras.

- VIII. de sacris Mercurii vel Jovis.

- IX. de sacrificio quod fit alicui sanctorum.

- X. de phylacteriis et ligaturis.

- XI. de fontibus sacrificiorum.

- XII. de incantationibus.

- XIII. de auguriis, vel avium vel equorum vel bovum stercore, vel sternutatione.

- XIV. de divinis vel sortilegis.

- XV. de igne fricato de ligno, id est nodfyr.

- XVI. de cerebro animalium.

- XVII. de observatione pagana in foco, vel in inchoatione rei alicujus.

- XVIII. de incertis locis quae colunt pro sacris.

- XIX. de petendo quod boni vocant sanctae Mariae.

- XX. de feriis quae faciunt Jovi vel Mercurio.

- XXI. de lunae defectione, quod dicunt Vinceluna.

- XXII. de tempestatibus et cornibus et cocleis.

- XXIII. de sulcis circa villas.

- XXIV. de pagano cursu quem yrias (Massmann's Form. 22: frias) nominant, scissis pannis vel calceis.

- XXV. de eo, quod sibi sanctos fingunt quoslibet mortuos.

- XXVI. de simulacro de consparsa farina.

- XXVII. de simulacris de pannis factis.

- XXVIII. de simulacro quod per campos portant.

- XXIX. de ligneis pedibus vel manibus pagano ritu.

- XXX. de eo, quod credunt, quia feminae lunam commendent, quod possint corda hominum tollere juxta paganos.

Evidently the mere headings of the chapters that formed the Indiculus itself, whose loss is much to be lamented. It was composed towards the middle of the 8th cent. among German-speaking Franks, who had adopted Christianity, but still mixed Heathen rites with Christian. Now that the famous Abrenuntiatio has been traced to the same Synod of Liptinae, we get a fair idea of the dialect that forms the basis here. We cannot look for Saxons so far in the Netherlands, beyond the Maas and Sambre, but only for Franks, whose language at that time partook far more of Low than of High German. I do not venture to decide whether these were Salian Franks or later immigrants from Ripuaria. (2)

Notes:

1. Conf. Hagen in Jrb. 2, 62. Liptinae, an old villa regia, afterw. Listines, in the Kemmerich (Cambresis) country, near the small town of Binche. [Back]

2. GDS. 537. ---EHM [Back]

Franken[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Friezen[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Fosite Uit Nederland zijn nauwelijks schriftelijke teksten bewaard gebleven. Alleen de god Fosite die op (waarschijnlijk) Helgoland werd vereerd wordt in de Vitae van Willibrord en Liudger genoemd. Uit de Vita van Liudger blijkt ook dat koning Radbod door middel van het werpen van het lot bepaalde of Liudgers metgezellen moetsen sterven of niet.

Saksen[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Van de religie van de Saksen is maar weinig bekend. De oudste gegevens stammen alle van de Frankische geschiedschrijvers, met name Einhard, die de verovering van het gebied der Saksen in de 8e eeuw beschreven. Niet al Einhards werk is bewaard gebleven, maar Adam van Bremen citeert hem in zijn Kerkgeschiedenis van Hamburg. Daardoor is er wat meer bekend over een belangrijk heiligdom van de Saksen, de Irminsul. Einhard beschreef deze als een grote boomstam. De naam betekende volgens hem "al-zuil" omdat hij als het ware de wereld ondersteunde. De Irminsul heeft wellicht parallellen met de Noordse Yggdrasill.

Karel de Grote liet de Irminsul in brand steken. Het goud dat aan de voet van de boom lag werd door de Franken geroofd. Karel vaardigde strenge wetten uit, de Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae, waarin het streng verboden werd de oude religieuze gewoonten te blijven aanhangen. Op sommige overtredingen stond de doodstraf.

In de Oudsaksische doopgelofte worden drie goden genoemd die de Saksen bij hun doop moesten afzweren: Thunaer ende Uoden ende Saxnote oftewel Donar, Wodan en de verder onbekende god [Saxnote]].

Hessen[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Ook van de Hessen is weinig bekend. Bonifatius was werkzaam in Hessen en hakte daar de Donareik om, om aan te tonen dat de heidense goden geen macht hadden. (

Zuidelijk Duitsland[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Merseburger toverspreuken Ziesburg? Gecorrumpeerde vorm van Ogesburg = Augsburg

Engeland[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Heldengedichten, toverspreuken, koningsgenealogieën Eostre Sutton Hoo

Noord-Europa[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Van de religie in de Scandinavische landen is vooral de mythologie goed bekend dankzij de Edda's en de Saga's die in IJsland werden opgetekend. Uit deze verhalen - die elkaar soms echter tegenspreken- komt een zeer uitgebreid pantheon naar voren met ingewikkelde verbanden. Er zijn twee belangrijke godenfamilies: de Asen en de Wanen. Er is sprake van meerdere werelden en naast de goden verscheidene andere soorten mythologische personen, zolas reuzen en dwergen. De centrale figuur is Odin. In de Noordse mythologie is er sprake van een eindtijd, wanneer de Ragnarök, de eindstrijd, zal plaatsvinden. Ook is er sprake van een hiernamaals, het Walhalla voor de gevallen strijders en een hel.

Denemarken[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

IJsland[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Noorwegen[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Zweden[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

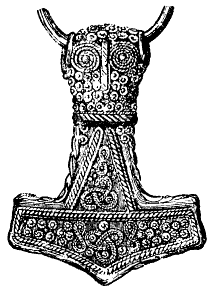

tempel van Uppsala vergulde beelden van Thor, Odin en Freyr (Fricco), mensenoffers, Adam van Bremen

Kerstening[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

De Germaanse religie werd uiteindelijk overal verdreven door het christendom, dat er actief voor streed het "heidense" geloof uit te roeien. De kerstening begon op verschillende plaatsen: in Engeland blablabla. Voor het Europese vasteland was vooral de bekering van de Frankische koning Clovis I (traditioneel in 486 geplaatst) van belang. In het kielzog van de veroveringen van zijn nazaten werden de onderworpen volkeren gedwongen tot het christendom over te gaan. Vooral onder Karel de Grote werd het aanhangen van eht oude geloof erg bemoeilijkt door de wetten die hij uitvaardigde, zoals het capitularium etc

De kerstening van de Angelsaksen begon met de aankomst van de eerste aartsbisschop van Canterbury, Augustinus, in 597. In 601 doopte hij koning Ethelbert van Kent. De laatse heidense koning in de heptarchie was Penda van Mercia (ovl. 655). De invloed van de niet-christelijke Noormannen bij hun invallen in de 9e eeuw Danelaw

Franken, Angelsaksen, Saksen, Denen, Zweden, Noren, wanneer?

Uitroeiing door de Kerk

Capitularium van Karel de Grote

Missionarissen

- Offers

- priesters

- vereringsplaatsen

- Goden

- archeologie

- parallellen met Romeinse goden

Overlevering elementen[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

De namen van de oude Germaanse goden leven nog voort in de namen van de dagen van de week. In het latijn zijn deze genoemd naar de toen 5 bekende planeten, de zon en de maan. Deze namen waren gelijk aan de namen van goden. Toen in de Germaanse streken de christelijke zevendaagse week werd ingevoerd werden de Latijnse namen naar hun lokale Germaanse equivalent vertaald. Dies Martis (dinsdag) werd in verscheidene landen genoemd naar de god *Tiwaz, in Nederland echter naar zijn werkzaamheid: de rechtspraak. Dies Mercurii (woensdag) werd genoemd naar zijn equivalent Wodan. Dies Iovi (donderdag) werd genoemd naar Jupiters equivalent Donar. De vrijdag (dies Veneris) werd genoemd naar Venus' equivalent Frija. Verder leven de namen van de goden voort in sommige plaatsnamen.

Bijgeloof[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Geloof in voortekens tot in de 19e eeuw in Oost-Nederland: -Hendrik Willem Heuvel: Uilen kondigen overlijden aan, katten komst van bezoek. Derk met de Beer. Witte Wieven (vermelding bij Sweder Schele

Onderzoek[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Germanic paganism refers to the religious beliefs of the Germanic peoples preceding Christianization. The best documented version of the Germanic pagan religions is 10th and 11th century Norse paganism, though other information can be found from Anglo-Saxon paganism and West German paganism. Scattered references are also found in the earliest writings of other Germanic peoples and Roman descriptions. The information can be supplemented with archaeological finds and remnants of pre-Christian beliefs in later folklore.

The Germanic religion was a polytheistic religion with some underlying similarities to other Indo-European traditions. The principal gods of Viking Age Norse paganism were Odin (Old Norse: Óðinn, Old High German language: Wodan, OE: Wōden) and Thor (North Germanic: Þórr, Old High German language: Donar, Old English language: Þunor). At an earlier stage, the principal god may have been Tiwaz (Old Norse language: Týr, Old High German language: Ziu, Old English language: Tiw).

Sources[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Most sources documenting Germanic paganism have presumably been lost. From Iceland there is a substantial literature, namely the Nordic Sagas and the Eddas, relating to the pagan period, but most of this was written long after Iceland's conversion to Christianity. Some information is found in the Nibelungenlied. The literary source closest to the pagan period may be Beowulf, which some scholars believe was composed as early as the eighth century , and therefore within the lifetime of pagans from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Suffolk, which remained officially pagan until 680. However, Beowulf is unlikely to have been composed in Suffolk, its creator was clearly Christian, and it reveals little or nothing about pagan beliefs or rituals. Limited information also exists in Tacitus' ethnographic work Germania.

Further material has been deduced from folk customs found in surviving rural folk traditions that have either been mildly superficially Christianized or lightly modified, including surviving laws and legislature (Althing, Anglo-Saxon law, the Grágás), calendar dates, customary folktales and traditional symbolism found in folk art.

A great deal of information has been unearthed by recent archaeology, including the Angl-Saxon pagan Sutton Hoo royal funerary site in East Anglia and the royal pagan temple at Gefren/Yeavering in Northumberland. The traditional ballads of the Northumbrian/Scottish borders, and their European counterparts, have also preserved many aspects of Germanic pagan belief. As York Powell wrote, "The very scheme on which the ballads and lays are alike built, the hapless innocent death of a hero or heroine, is as heathen as the plot of any Athenian tragedy can be."

The majority of the literary evidence for Germanic paganism was likely intentionally destroyed when Christianity slowly gained dominant political power in Anglo-Saxon England, then Germania and later Scandinavia throughout the Middle Ages. Although perhaps singularly most responsible for the destruction of pagan sites, including purported massacres such as the Massacre of Verden and the subsequent dismantling of ancient tribal ruling systems, the Frankish emperor Charlemagne of The Holy Roman Empire is said to have acquired a substantial collection of Germanic pre-Christian writings, which was deliberately destroyed after his death.[bron?]

Pre-Migration Period[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Caesar[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

The earliest forms of the Germanic religion can only be speculated on based on archaeological evidence and comparative religion. The first written description is in Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico. He contrasts the elaborate religious custom of the Gauls with the "primitive" Germanic traditions.

The Germans differ much from these usages, for they have neither Druids to preside over sacred offices, nor do they pay great regard to sacrifices. They rank in the number of the gods those alone whom they behold, and by whose instrumentality they are obviously benefited, namely, the sun, fire, and the moon; they have not heard of the other deities even by report. — The Gallic War (6.21)[4]

Caesar's description contrasts with other information on the early Germanic tribes and is not given much weight by modern scholars. It is worth mentioning his note that Mercury is the principal god of the Gauls:

They worship as their divinity, Mercury in particular, and have many images of him, and regard him as the inventor of all arts, they consider him the guide of their journeys and marches, and believe him to have great influence over the acquisition of gain and mercantile transactions. — The Gallic War (6.17)[5]

The worship of deities identified by the Romans with Mercury seems to have been prominent among the northerly tribes.

Tacitus[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

A much more detailed description of Germanic religion is Tacitus' Germania, dating to the 1st century.

Tacitus describes both animal and human sacrifice. He identifies the chief Germanic god with the Roman Mercury, who on certain days receives human sacrifices, while gods identified by Tacitus with Hercules and Mars receive animal sacrifice. The largest Germanic tribe, Suebians also make sacrifices, allegedly of captured Roman soldiers, to a goddess who is identified by Tacitus with Isis.

Another goddess, Nerthus, is revered as the Earth Mother by Reudignians, Aviones, Angles, Varinians, Eudoses, Suardones and Nuithones. Nerthus is believed to directly interpose in human affairs. Her sanctuary is on an island, specifically in a wood called Castum. A chariot covered with a curtain is dedicated to the goddess, and only the high priest may touch it. The priest is capable of seeing the goddess enter the chariot. Drawn by cows, the chariot travels around the countryside and wherever the goddess visits, a great feast is held. During the travel of the goddess, these tribes do not go to war and touch no arms. When the priest declares that the goddess is tired of conversation with mortals, the chariot returns and is washed, together with the curtains, in a secret lake. The goddess is also washed. The slaves who administer this purification are afterwards thrown into the lake.[6]

According to Tacitus, the Germanic tribes think of temples as being unsuitable habitations for gods, and they do not represent them as idols in human shape. Instead of temples, they consecrate woods or groves to individual gods.

Divination and augury was very popular:

To the use of lots and auguries, they are addicted beyond all other nations. Their method of divining by lots is exceedingly simple. From a tree which bears fruit they cut a twig, and divide it into two small pieces. These they distinguish by so many several marks, and throw them at random and without order upon a white garment. Then the Priest of the community, if for the public the lots are consulted, or the father of a family about a private concern, after he has solemnly invoked the Gods, with eyes lifted up to heaven, takes up every piece thrice, and having done thus forms a judgment according to the marks before made. If the chances have proved forbidding, they are no more consulted upon the same affair during the same day: even when they are inviting, yet, for confirmation, the faith of auguries too is tried. Yea, here also is the known practice of divining events from the voices and flight of birds. But to this nation it is peculiar, to learn presages and admonitions divine from horses also. These are nourished by the State in the same sacred woods and groves, all milk-white and employed in no earthly labour. These yoked in the holy chariot, are accompanied by the Priest and the King, or the Chief of the Community, who both carefully observed his actions and neighing. Nor in any sort of augury is more faith and assurance reposed, not by the populace only, but even by the nobles, even by the Priests. These account themselves the ministers of the Gods, and the horses privy to his will. They have likewise another method of divination, whence to learn the issue of great and mighty wars. From the nation with whom they are at war they contrive, it avails not how, to gain a captive: him they engage in combat with one selected from amongst themselves, each armed after the manner of his country, and according as the victory falls to this or to the other, gather a presage of the whole.

The reputation of Tacitus' Germania is somewhat marred as a historical source by the writer's rhetorical tendencies. The main purpose of his writing seems to be to hold up examples of virtue and vice for his fellow Romans rather than give a truthful ethnographic or historical account, although modern day scholars are reverting this point of view as unholdable.[7] But while Tacitus' interpretations are sometimes dubious, the names and basic facts he reports are credible; Tacitus touches on several elements of Germanic culture known from later sources. Human and animal sacrifice is attested by archaeological evidence and medieval sources. Rituals tied to natural features are found both in medieval sources and in Nordic folklore. A ritual chariot or wagon as described by Tacitus was excavated in the Oseberg find. Sources from medieval times until the 19th century point to divination by making predictions or finding the will of the gods from randomized phenomena as an obsession of Germanic cultures. Or as Tacitus puts it "To the use of lots and auguries, they are addicted beyond all other nations."

While there is rich archaeological and linguistic evidence of earlier Germanic religious ideas, these sources are all mute, and cannot be interpreted with much confidence. Seen in light of what we know about the medieval survival of the Germanic religions as practiced by the Nordic nations, some educated guesses may be made. However, the presence of marked regional differences make generalization of any such reconstructed belief or practice a risky venture.

Migration Period[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

During the Migration Period, Germanic religion was subject to syncretic influence from Christianity and Mediterranean culture (see also Runes, Erilaz).

Jordanes' Getica is a 6th century account of the Goths, written a century and a half after Christianity largely replaced the older religions among the Goths. According to the Getica, the chief god of the Goths was Mars, who they believed was born among them:

Now Mars has always been worshipped by the Goths with cruel rites, and captives were slain as his victims. They thought that he who is the lord of war ought to be appeased by the shedding of human blood. To him they devoted the first share of the spoil, and in his honor arms stripped from the foe were suspended from trees. And they had more than all other races a deep spirit of religion, since the worship of this god seemed to be really bestowed upon their ancestor. — Getica

Saint Columbanus in the 6th century encountered a beer sacrifice to Woden in Bregenz. In the 8th century, the Germanic Saxons venerated an Irminsul (see also Donar's Oak). Charlemagne is reported to have destroyed the Saxon Irminsul in 772.

In the Old High German Merseburg Incantations, the only pre-Christian testimony in the German language, appears a Sinhtgunt who is the sister of the sun maiden Sunna (Sól). She is not known by name in Nordic mythology, and if she refers to the moon, she is then different from the Scandinavian (Mani), who is male. Further, Nanna is mentioned.

The Goths were converted to Arianism in the 4th century, contemporaneous to the adoption of Christianity by the Roman Empire itself (see Constantinian shift).

Unfortunately, due to their early conversion to Christianity, little is known about the particulars of the religion of the East Germanic peoples, separated from the remaining Germanic tribes during the Migration period. Such knowledge would be suited to distinguish Proto-Germanic elements from later developments present in both North and West Germanic.

The Franks, Alamanni, Anglo-Saxons, Saxons, and Frisians were Christianized between the 6th and the 8th century. By the end of the Migration period, only the Scandinavians remained pagan.

Viking Age[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Early medieval North Germanic Scandinavian (Viking Age) paganism is much better documented than its predecessors, notably via the records of Norse mythology in the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda, as well as the sagas, written in Iceland during 1150 - 1400.

Sacrifices were known as blót, seasonal celebrations where gifts were offered to appropriate gods, and attempts were made to predict the coming season. Similar events were sometimes arranged in times of crisis, for much the same reasons.[8][9]

The goddess Frijja seems to have split into the two different, clearly related goddesses Frigg and Freyja. In Nordic mythology there are certain vestiges of an early stage where they were one and the same, such as husbands Óðr/Óðinn, their shamanistic skills and Freyja/Frigg's infidelity.[10]

Middle Ages[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

In 1000 AD, Iceland became nominally Christian, although continuation of pagan worship in private was tolerated. Most of Scandinavia was Christianized during the 11th century. Adam von Bremen gives the last report of vigorous Norse paganism.[11] Sometimes, the subjects of a lord who converted to Christianity refused to follow his lead (this happened to the Swedish kings Olof of Sweden, Anund Gårdske and Ingold I) and would sometimes force the lord to rescind his conversion (e.g. Haakon the Good).[12] The attempt of the deposed Christian monarch Olaf II of Norway to retake the throne resulted in a bloody civil war in Norway, which ended in the battle of Stiklestad (1030). In Sweden, in the early 1080s, Inge I was deposed by popular vote for not wanting to sacrifice to the gods, and replaced by his brother-in-law Blot-Sweyn (literally "Sweyn the Sacrificer").[13] After three years of exile, Inge returned in secret to Old Uppsala and during the night the Christians surrounded the royal hall with Blot-Sweyn inside and set it on fire.[14][15] However, Inge did not immediately regain his throne and the pagan Eirik Arsale briefly came into power[16] before being usurped by Inge.

During the High Middle Ages, Scandinavian paganism became marginalized and blended into rural folklore. In folklore and legend, elements of Germanic mythology survived, and appears in the guise of fairy tales such as those collected by the Brothers Grimm and other folk tales and customs (see Walpurgis Night, Holda, Berchta, Weyland, Krampus, Lorelei, Nix), as well as in medieval courtly literature (Nibelungs).

Modern Influence[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

| Day | Origin |

|---|---|

| Monday | Moon's day |

| Tuesday | Tiw's day |

| Wednesday | Wóden 's day |

| Thursday | Þunor's day |

| Friday | Freyr's day |

| Sunday | Sun's day |

The Germanic gods have affected elements of every day western life in most countries that speak Germanic languages. An example is some of the names of the days of the week. The days were named after Roman gods in Latin (named after Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Saturn). The names for Tuesday through Friday were replaced with Germanic versions of the Roman gods. In English and Dutch, Saturn was not replaced. Saturday is named after the Sabbath in German, and is called "washing day" in Scandinavia.

Also, many place names such as Woodway House, Wansdyke, Thundersley and Frigedene are named after the old deities of the English people.

Reconstructie[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Elements of common Germanic mythology and religion may be reconstructed from elements common to North and West Germanic, see common Germanic deities.

Zie ook[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

Noten[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

- ↑ Julius Caesar De bello Gallico boek VI.21 Online

- ↑ http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/origo.html

- ↑ Jordanes Getica 40-41 [ttp://www.thelatinlibrary.com/iordanes1.html Latijnse tekst], ~Engelse vertaling

- ↑ De Bello Gallico, Liber VI (in Latin)

- ↑ De Bello Gallico, Liber VI (in Latin)

- ↑ Tacitus' Germania, Chapter 40

- ↑ Tacitus' Germania in English translation...

- ↑ See Viga-Glum’s Saga (Ch.26), Hakon the Good’s Saga (Ch.16), Egil’s Saga (Ch. 65), etc.

- ↑ Adam of Bremen. Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae pontificium Book IV, Ch.26-28.

- ↑ Davidson, H.R. Ellis (1965). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin, p. 110-124. ISBN 978-0140136272.

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Þorgilsson, Ari. Íslendingabók, Ch.7, etc..

- ↑ Saga of Sigurd the Crusader and His Brothers Eystein and Olaf Ch.28, etc.

- ↑ Orkneyinga saga

- ↑ For a slightly different account of the same incident see The Saga of Hervör and Heithrek (c. 1325), in translation by Nora Kershaw.

- ↑ ibid

Literatuur[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

- Alkarp, Magnus, Tempel av guld eller kyrka av trä? Markradarundersökningar vid Gamla Uppsala kyrka. (2005).

- Peter Buchholz (1968) Perspectives for Historical Research in Germanic Religion, History of Religions, vol. 8, no. 2, 111-138.

Categorie:Germaanse mythologie

Categorie:Indo-Europese mythologie

ca:Llista de personatges, objectes i llocs de la mitologia germànica da:Germansk religion de:Germanische Mythologie es:Mitología germana fr:Mythologie germanique fy:Germaanske mytology ru:Германская мифология fi:Germaaninen mytologia vls:Germoansche mythologie